Making Diamonds more Beautiful than ever

In my last blog post, which I called “Diamonds Growing on my Family Tree”, I explained a little of my family history connected to the diamond world, and showed the scales used around the world to gauge the color and clarity of a diamond. With a photo of some rough diamond crystals I purchased in Antwerp in the 1990’s I explained how a diamond cutter takes two diamonds out of one crystal and, depending on how the cutting company perceives diamonds – as objects of wonder and beauty, or merely as vehicles to profit – the object of the company may be to cut diamonds “ideally” or to set about to retain as much weight from the original crystal as the cutter can squeeze, compromising the beauty in the process.

The Laws of Physics Applied to Diamonds

I believe in the power of a diamond to be infinitely more beautiful when certain laws of physics are applied in the cutting process, laws of science that describe what light does as it travels through space and different media, how much it bends and how much color it gives off as it bends when entering and exiting a medium of travel (such as air, water, gas or crystal).

In this drawing you can see the path of light one beam of light takes through a perfectly cut diamond. The diamond in the drawing sits face up to a light source directly over it. To the right of the light source is an eyeball of an imaginary observer who is seeing the ray of light coming from the light source through the medium of the diamond. The light takes a straight path to the diamond, passes through the table (large facet on top) of the diamond and strikes a facet on the bottom of the diamond.

In this drawing you can see the path of light one beam of light takes through a perfectly cut diamond. The diamond in the drawing sits face up to a light source directly over it. To the right of the light source is an eyeball of an imaginary observer who is seeing the ray of light coming from the light source through the medium of the diamond. The light takes a straight path to the diamond, passes through the table (large facet on top) of the diamond and strikes a facet on the bottom of the diamond.What happens next to the beam of light depends completely on the angle of the facet it strikes. If the facet it strikes is parallel to the table, the light will pass through that facet, out the diamond and the observer will see no magic colors, no brilliant reflection, nothing special. If the facet is at an angle of approximately 40.75 degrees to the table facet, the light will be bent in such a way as to NOT LEAVE THE DIAMOND and jump across the bottom of the diamond to another facet opposite it.

If that opposite facet is placed at the perfect angle, the light will be bent again, this time upward inside the diamond and still will not leave the diamond; instead it will strike a facet above the last one it struck. If that upper facet is placed at approximately 34.50 degrees to the table facet, the light will be bent one more time as it passes through the top of the diamond and, in the process of refracting (bending) and exiting, will fire off a rainbow of color, literally. The beam of white light will, upon exiting the diamond, be broken down into the color spectrum in the same order as the colors appear in a rainbow having used the diamond as a prism.

Who Formulated these Proportions and Angles?

The pure scientists who looked at diamonds with their objective bent over the centuries postulated there was some set of proportions that would lead diamonds to give off their best light show, proportions that were ideal for light entering carbon crystals which are what diamonds are. All substances bend light differently. Or, put another way, each material has a particular degree to which it refracts light and is categorized thusly by its “refractive index”. Diamond and zirconium have very high refractive indices and, when cut right, put on amazing light shows.

Scientists speculated, formulated, prophesized and argued about the proportions to which a diamond had to be cut in order to be its most beautiful for centuries until one Belgian scientist, a mathematician and physicist who studied at the University of London named Marcel Tolkowsky, picked up a tang (diamond cutting instrument) and put it to the wheel (the diamond dust-incrusted spinning metal plate that abrades the surface of diamonds) in the New York factory of Lazare Kaplan early in the 20th century. Kaplan was Tolkowsky’s cousin and was extremely interested in the outcome of his cousin’s experiments, hoping to get a stranglehold on the future of cutting diamonds to ideal proportions.

Scientists speculated, formulated, prophesized and argued about the proportions to which a diamond had to be cut in order to be its most beautiful for centuries until one Belgian scientist, a mathematician and physicist who studied at the University of London named Marcel Tolkowsky, picked up a tang (diamond cutting instrument) and put it to the wheel (the diamond dust-incrusted spinning metal plate that abrades the surface of diamonds) in the New York factory of Lazare Kaplan early in the 20th century. Kaplan was Tolkowsky’s cousin and was extremely interested in the outcome of his cousin’s experiments, hoping to get a stranglehold on the future of cutting diamonds to ideal proportions.Tolkowsky was trying to find the right angles and proportions, measuring as effectively as science allowed with its unsophisticated instruments of the day. He measured only the outside of diamonds, theorizing about light, but did not actually follow the path light was taking with the instrumentation that was to appear in gemological circles and cutting factories toward the end of the 20th century. His treatise about the enhancement of brilliance and fire produced by cutting to ideal proportions had merit and proved to be absolutely true.

The so-called Ideal Cut

Mr. Tolkowsky did not live long enough to see how true his ideas were nor how far he was from proving it since his proof relied only on measurements taken on the surfaces of diamonds. Here is one institution’s sense of what constitutes ideal based heavily, but not entirely, on what Tolkowsky proposed as ideal cutting standards:

The Firescope—First big Breakthrough

In a later blog post I will tell the story of how some of today’s instrumentation came to exist since it is vital to understanding today’s diamond revolution and the role I played in it, but for now I just want to shed light on a device called the Firescope that allowed people with no background in gemology or physics to see with just their eye how well or poorly a diamond was cut. The Firescope was invented in Japan

|

| Here is how the Firescope achieves this "light study" |

It was designed to send light into a diamond that was red in color to see how much red light came back out of the diamond. Red in was the beginning of the path of light. Red light back out indicated light did not pass through the diamond, but was REFLECTED back out the top of it causing brilliance to occur.

Many years after we began cutting diamonds to make them appear correct in the Firescope, I commissioned a man with two degrees in physics from MIT to make me a scope (we called it the Dispersionscope in the beginning) that showed graphically how much FIRE a diamond was producing because the two most important elements of a diamond’s beauty are fire and brilliance.

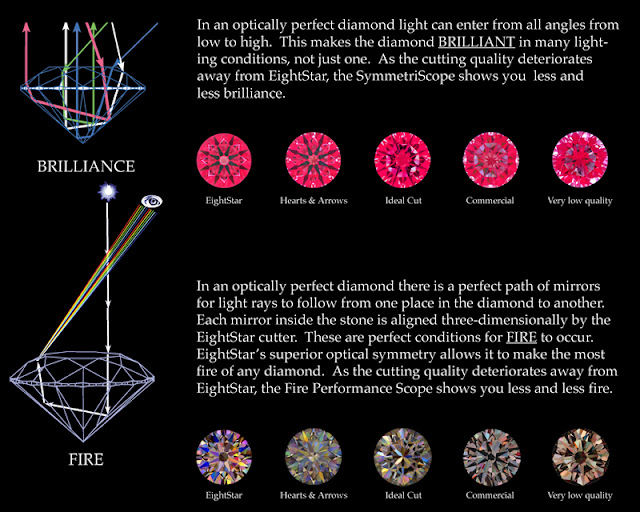

Here is a visual representation of these two concepts at work in a diamond with photographs taken through each instrument to demonstrate both brilliance and fire in diamonds:

Notice on the chart above that there is a diamond labeled “Ideal Cut” but there are two cuts better than it. How can a cut be better than ideal? Until the invention of these devices (the Firescope and the Dispersionscope) measurements from the exterior of a diamond were sufficient to grade the diamond’s cut. Once people saw that it was OPTICAL symmetry that made a diamond right – and that correct proportions measured from the outside did not necessarily reflect on a diamond’s optical, three-dimensional symmetry – the concept of ideal cutting was immediately antiquated and relegated to a former era of gemology. Much more about this later.

The diamonds we cut in my factory, Eightstar diamonds, were the best in the world because they were the first diamonds ever cut to actually hit the target that Tolkowsky sensed was correct, that actually demonstrated superiority in beauty because of superiority in optically aligned cutting.

When you look at the brilliance images above, you can see white light coming through the diamonds (indicating loss of brilliance) on the right, but not on the left. When you look at the fire images above, you can see less and less fire emanating from the diamonds on the right as the optical symmetry of the diamonds deteriorates.

In my next blog post I will explain how we came to learn how to cut diamonds from a master cutter in Japan